(gap: 2s) My younger days unfolded in a setting that, at first glance, might have been drawn from the pages of a cherished family magazine. Our home was a spacious, sunlit house, its walls adorned with cheerful wallpaper and shelves displaying blue and white china plates. The air was often filled with the sound of youngsters’s laughter, the gentle patter of feet on polished floorboards, and the delicate clink of teacups in the afternoon. Yet, beneath this idyllic surface, there existed a set of rules and a discipline as certain as the rising of the sun.

From my earliest days, I was aware of a peculiar curiosity within myself—a secret interest in the world of discipline, and, in particular, the ritual of corporal punishment. At the time, I could not have named it, nor understood its true nature. Instead, I felt a deep sense of confusion and shame, as though I were a character in a story who had wandered off the proper path. I believed, with the earnestness of a youngster, that my secret rendered me unworthy of love or heaven’s embrace. Thus, I kept it locked away, hidden even from my closest companions.

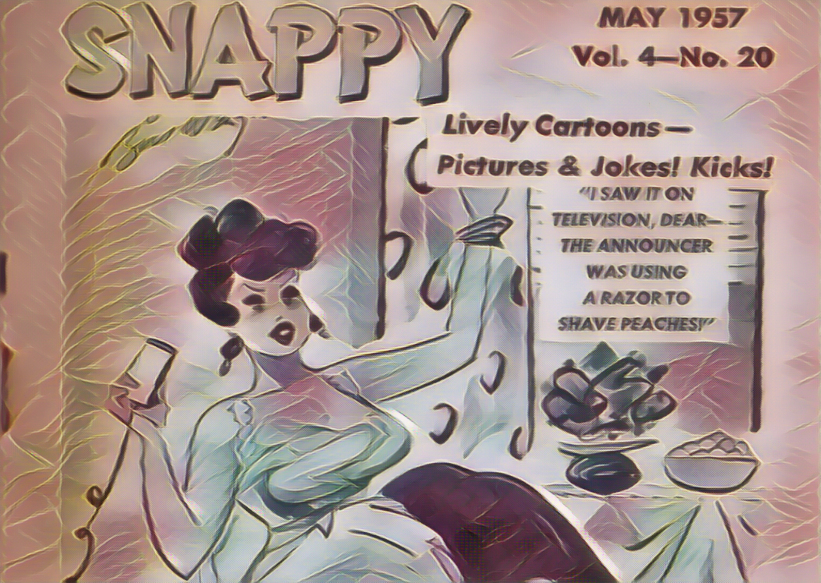

The environment in which I was raised seemed almost designed to nurture this secret. In our community, discipline was not merely accepted—it was celebrated, woven into the very fabric of daily life. I recall, with vivid clarity, the solemn hush that would fall over the congregation as a tape played in both church and home, its message unwavering: “Spare the rod and spoil the child.” The adults nodded in agreement, and we all listened, wide-eyed, to tales of wayward boys and girls set right by a firm hand.

Our household was a bustling, ever-changing tapestry of people. My father, a tall and dignified man, presided over the family with gentle authority. There was my mother, whom I shall call Mother Prudence, and my father’s other wives—Mother Beth, with her quick smile and efficient manner, and Mother Anne, whose calm presence filled the kitchen with warmth. At any given time, there might be a dozen or more youngsters under our roof, their ages ranging from toddling infants to near-grown youths. The older ones, too, were sometimes called upon to assist in matters of discipline, and even the principal at our little school—a stern gentleman with a bristling moustache—was known to wield the rod.

Each adult had their own particular style, as distinct as the patterns on the parlour curtains. The principal, Mr. Hargreaves, was a figure of awe and respect. He would enter the classroom, yardstick in hand, and with a flourish reminiscent of a headmaster in a boarding school story, deliver swift justice to anybody caught misbehaving. The sharp sound of wood on palm or calf would echo down the corridor, and we would whisper about the red marks that sometimes appeared, badges of mischief and consequence.

My father, for all his sternness, was a man of measured discipline. When one of us was summoned to his study—a room lined with books and the faint scent of pipe tobacco—it was considered the gravest of occasions. We would be told to bend over the polished desk, and Father would administer a set number of strokes with his belt, never more than our years in age. Though the ritual was solemn, and the shame of being sent to Father keenly felt, his hand was not as heavy as some, and the ordeal was often more about reflection than pain.

Mother Beth, on the other hand, was brisk and efficient. Her punishments were swift affairs, delivered with a practiced hand and a no-nonsense air. She would sit on the edge of her bed, call the errant culprit to her side, and in a matter of moments, the deed was done. The sting would linger, but so too would her gentle words of encouragement, as if to say, “All is forgiven, now run along and play.” There was a certain comfort in the regularity of her discipline, like the chime of the clock marking the hours.

Mother Anne, the heart of our kitchen, favoured a wooden spoon for her rare but memorable punishments. She was a patient teacher, guiding the older girls through the mysteries of baking and preserving, and it was usually these helpers who found themselves on the receiving end of her discipline. I remember the nervous anticipation as she would tap the spoon against her palm, her eyes twinkling with both mischief and affection. I, being more often in the garden or the schoolroom, escaped her attention for the most part, though I recall a handful of occasions when I, too, was summoned for a gentle reminder.

My own mother, Mother Prudence, was a woman of deep feeling and quiet strength. Her approach to discipline was thoughtful and deliberate. When one was called to her—always by name, over the intercom that echoed through the house—it was a moment of great solemnity. “Corby is to see Mother Prudence in the first floor bathroom,” the voice would announce, and the chosen one would make their way, heart pounding, to the appointed place.

Each bathroom was furnished with a sturdy chair, and Mother would be waiting, her hands folded in her lap. She would draw the culprit close, recounting their misdeeds in a gentle but firm tone, before guiding them over her knee. Her punishments were not hurried; they were measured, interspersed with words of guidance and, sometimes, a quiet prayer. She believed in what she called “broken compliance”—the moment when a culprit’s resistance melted away, replaced by tears and heartfelt apologies. Afterwards, there would be a time for reflection, and always, a warm embrace.

(pause) But it was on one particular afternoon, when the sun shone golden through the parlour windows and the air was thick with the scent of summer, that the slipper incident occurred—a scene that remains etched in my memory as vividly as any adventure from the pages of a beloved book. (short pause) We all, filled with the excitement of forbidden play, had taken to playing football in the parlour, our laughter ringing out as the ball darted between us like a mischievous sprite. Suddenly, with a crash that seemed to silence even the birds outside, the ball struck a vase, sending it tumbling to the floor in a shower of water and petals.

(pause) In that instant, all merriment ceased. Our hearts thudded in our chests as we gazed at the ruin before us, knowing full well the gravity of our mischief. It was then that Mother Beth appeared in the doorway, her eyes both stern and sparkling with a curious mixture of disappointment and affection. “Well, well,” she said, her voice calm but resolute, “it seems the parlour is not a football pitch after all.” (short pause) She beckoned us forward, and though our feet felt as heavy as lead, we obeyed, heads bowed in contrition.

(pause) Mother Beth seated herself upon the edge of the bed, her posture upright and dignified, and reached for her slipper—a well-worn, sensible thing, soft at the toe but firm at the heel. One by one, we were called to her side. I remember the peculiar flutter in my stomach as my name was spoken, the mixture of apprehension and a strange, inexplicable anticipation. She took my hand gently, guiding me across her lap, and spoke in a low, even tone about the importance of respecting the home and the trust placed in us.

(pause) The punishment itself was neither cruel nor hurried. The slipper landed with a brisk, rhythmic sound, each swat stinging but never truly hurting, as if to remind rather than to punish. I felt my cheeks grow warm, both from the sting and from the knowledge that my siblings watched, their own faces a mixture of sympathy and relief that their turn was yet to come. Tears pricked at my eyes, not from pain, but from the weight of disappointment and the earnest desire to be good.

(pause) When it was over, Mother Beth set aside the slipper and drew me into a gentle embrace. “There now,” she murmured, smoothing my hair, “all is forgiven. Off you go, and remember—adventures are best had outdoors.” Her words, so kind and understanding, seemed to lift the heaviness from my heart. I rejoined my brothers and sisters, who offered shy smiles and quiet words of comfort, and together we tidied the parlour, our spirits lighter for the lesson learned.

(pause) The consequences of that afternoon lingered, not as a shadow, but as a gentle reminder of the boundaries that shaped our world. We spoke of the incident in hushed tones for days, each of us vowing to be more careful, and to keep our games to the garden where they belonged. Yet, in the years that followed, I often looked back on that day with a curious fondness, recalling not only the sting of the slipper, but the warmth of forgiveness and the sense of belonging that came from being guided, ever so gently, back onto the right path.

(pause) As I grew older and eventually left that world behind, I discovered, to my astonishment, that I was not alone. The wonders of the modern age revealed a community of kindred spirits, each with their own stories and secrets. I found comfort in their company, and, in time, learned to embrace the parts of myself I had once hidden away. Now, when I look back on those days—the sunlit rooms, the gentle voices, the rituals of discipline—I see them not only as moments of pain, but as threads in the tapestry of my life, woven with both sorrow and joy. And, in a curious way, I have found that revisiting those memories, with friends who understand, has brought me a measure of healing that even the wisest of doctors could not provide.