(gap: 2s) My name is Peter, and as a child in the early 1970s, I lived on a sprawling council estate in Surrey—a place where the houses were all the same shade of pebble-dash grey, and the gardens were separated by rickety wooden fences that seemed to lean in sympathy with the wind. The estate was a world unto itself, a patchwork of narrow streets, communal greens, and the ever-present hum of children’s laughter echoing between the rows of houses. In those days, the boundaries between families were porous; neighbours watched over each other’s children, and discipline was a communal affair. If you misbehaved, it wasn’t just your parents you had to worry about—any adult could step in, and they often did. Aunt Betty, who lived just a few doors down, was the undisputed matriarch of our little corner, and she took her role as enforcer of good behaviour very seriously.

The custom of calling every adult “Aunty” or “Uncle” was as much a part of our lives as the taste of jam sandwiches or the smell of cut grass after rain. It didn’t matter if they were blood relatives or not; the title was a badge of respect, a way of acknowledging the authority of grown-ups in a world where children were expected to be seen and not heard. I was always told to call her Aunty Betty, though sometimes the words stuck in my throat. I couldn’t help but wonder if these adults truly deserved our deference. Many of them, despite their humble circumstances, carried themselves with an air of self-importance that bordered on arrogance. They could be brusque, even rude, and yet the ritual of respect was so deeply ingrained that to question it felt like heresy. Still, I played along, even as I nursed private doubts and a quiet resentment that simmered just beneath the surface.

My closest companions were Dennis and Gavin, Aunt Betty’s twin sons. We spent endless hours together, our days a blur of scraped knees, muddy shoes, and wild games that spilled from back gardens onto the estate’s communal green. I was never much good at football—my coordination left a lot to be desired, and I secretly dreaded the moments when the ball came my way. But I played anyway, desperate to fit in, to be one of the boys, even if I always felt a step behind. Dennis and Gavin were identical in appearance—both with mop-top haircuts and mischievous grins—but their personalities couldn’t have been more different. Dennis was loud, opinionated, and quick to offer his thoughts on any subject, his voice carrying the nasal twang of Zippy from Rainbow. Gavin, on the other hand, was quieter, his ginger hair and freckles giving him a look of innocence that belied his sly sense of humour. He was a master of subtle mischief, always ready with a clever trick or a whispered dare. The two of them were locked in a perpetual contest, each trying to outdo the other in feats of speed, strength, or cunning. But when I was around, their rivalry faded; I was no competition, and they seemed to enjoy having someone to best without even trying. Our friendship was forged in the long, golden afternoons of summer, when the days stretched on forever and the world felt both vast and safe.

Aunt Betty ruled her household with a firm hand. Her husband, also named Dennis, was away working abroad, leaving her in sole command. She was a formidable presence—tall, broad-shouldered, with a voice that could cut through the din of a dozen children at play. She had a reputation for fairness, but also for strictness. She never hesitated to discipline her sons, and it seemed that not a day went by without one or both of them receiving a smack for some infraction. Yet, she was always kind to me, greeting me with a smile and a plate of biscuits, even as she kept a watchful eye on our antics.

One particular summer afternoon stands out in my memory, as vivid now as it was then. The sun hung low in the sky, casting long shadows across the garden, and the air was thick with the scent of honeysuckle and freshly cut grass. The three of us—Dennis, Gavin, and I—were playing football in their back garden, our shouts and laughter rising above the hum of distant lawnmowers. The garden was a patchwork of worn grass and flowerbeds, bordered by a greenhouse that gleamed in the sunlight. We played with reckless abandon, heedless of the fragile glass panes that stood just a few feet from our makeshift goal. It was only a matter of time before disaster struck. With a wild swing of my foot, I sent the ball hurtling towards the greenhouse. There was a sharp, crystalline crash as the ball shattered a pane of glass, and for a moment, time seemed to stand still. We stared at the broken window in horror, the silence broken only by the distant barking of a dog.

Aunt Betty’s voice rang out, sharp and commanding, calling Dennis and Gavin inside. My heart pounded in my chest as I watched them disappear into the house, their heads bowed in anticipation of what was to come. I lingered for a moment, unsure of what to do, then slipped away, hoping that my role in the accident would be forgotten. That night, I lay awake in bed, replaying the scene over and over in my mind, the sound of breaking glass echoing in my ears.

The next morning, I found Dennis and Gavin waiting for me by the swings. Their faces were solemn, and they spoke in hushed tones, glancing over their shoulders as if afraid Aunt Betty might appear at any moment. They told me, with a mixture of pride and resentment, that they had both received a spanking for breaking the greenhouse glass. I could see the faint traces of tears in their eyes, and for a moment, I felt a pang of guilt. Before we could discuss it further, another friend arrived, and the conversation shifted to other, safer topics.

We spent the morning playing in the garden, avoiding football and sticking to games that seemed less likely to end in disaster. The air was filled with the sound of laughter and the clatter of skipping ropes, but beneath the surface, I could sense a tension, a shared secret that bound us together. Suddenly, Aunt Betty appeared at the back door, her expression unreadable. She called my name, her voice calm but firm, and beckoned me inside. My stomach twisted with anxiety as I followed her, the laughter of my friends fading behind me.

Inside, the house was cool and dim, the air heavy with the scent of lavender polish and boiled cabbage. Aunt Betty led me to the lounge, her grip gentle but unyielding. She explained, in measured tones, that both Dennis and Gavin had been punished for the broken glass, and that she believed it was only fair that I should be held accountable as well. Her words were matter-of-fact, devoid of anger, but I could sense the weight of her expectations pressing down on me.

She asked if I agreed with her assessment, and I felt trapped, caught between the desire to protest my innocence and the fear of making things worse. I nodded, my voice barely more than a whisper. Aunt Betty offered me a choice: she could either inform my parents, or she could deal with the matter herself. The thought of my parents finding out filled me with dread—they were strict, and their punishments were never mild. Reluctantly, I agreed to let Aunt Betty handle it, hoping that her reputation for fairness would work in my favour.

The house was larger than most on the estate, a rambling structure with creaking floorboards and the faint smell of damp in the corners. The boys’ grandparents lived downstairs, their presence a constant but silent backdrop to the chaos of daily life. Aunt Betty, Dennis, and Gavin occupied the upper floors, their rooms filled with the detritus of childhood—comic books, toy cars, and the ever-present hum of a transistor radio playing the latest hits from the charts.

As Aunt Betty led me towards the kitchen, the phone rang, its shrill tone cutting through the stillness. She paused to answer it, leaving me standing alone in the hallway. I glanced down at my feet, suddenly aware of the rule against outdoor shoes in the house. I slipped them off, my socks whispering against the cool linoleum as I waited, nerves jangling.

My anxiety grew as Dennis, Gavin, and another boy drifted into the room, their eyes wide with curiosity. I hoped Aunt Betty would send them away, sparing me the humiliation of being punished in front of an audience. But when she returned, she made it clear that privacy was not an option. She never punished her own sons in secret, and she wasn’t about to make an exception for me. My protests died on my lips as she took me by the arm and led me into the kitchen, the others trailing behind.

The kitchen was a battleground of linoleum and Formica, the air thick with the lingering aroma of last night’s dinner. In the centre of the room stood an upright chair, its wooden back polished smooth by years of use. Aunt Betty, her hair wound tightly in curlers and her lips pursed in a look of grim determination, stood beside it like a judge preparing to pass sentence. She instructed me to kneel on the seat and grip the back of the chair, my knuckles turning white as I obeyed. My heart hammered in my chest, each beat echoing in my ears like a drum. The boys watched from the doorway, their faces a mixture of sympathy and anticipation.

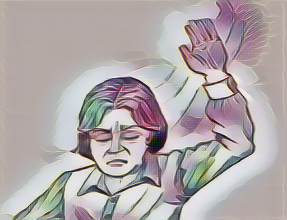

Aunt Betty’s voice was solemn as she announced my sentence: a spanking with her hand, followed by six with the slipper, since I was the eldest and therefore, in her eyes, the most responsible. I tried to appear brave, but my knees shook and my mouth went dry. She made sure I was holding the chair properly, her hands firm on my shoulders, leaving no room for escape. Then, with a swift, practiced motion, she began. Her hand was heavy and unerring, each smack landing with a sharp sting that reverberated through my body. The sound echoed off the tiled walls, mingling with the muffled gasps of the boys in the doorway. I clenched my teeth, determined not to cry, but by the third or fourth blow, tears pricked at the corners of my eyes. My cheeks burned with shame, and my resolve crumbled.

(short pause) Just when I thought the ordeal was over, Aunt Betty reached for her slipper—a battered, tartan relic that had achieved near-mythical status among the children of the estate. The red and green checks were faded, the fabric worn thin and frayed at the edges. The sole was patched with ancient glue, and the inside was lined with a scratchy material that had long since lost its softness. The heel was flattened from years of use, and the whole thing carried the faint, musty scent of old carpet and lavender polish. This was no ordinary slipper; it was Aunt Betty’s weapon of choice, a symbol of her authority and a source of dread for every child who crossed her path. She slipped it off with a flourish, her eyes never leaving mine, and delivered six solid whacks. Each one landed with the force of a thunderclap, sending fresh waves of pain through my already stinging backside. I yelped, unable to contain my distress, and by the final stroke, I was sobbing openly, my pride in tatters. In the next room, I imagined Dennis, Gavin, and the others listening, their faces twisted in sympathy—or perhaps amusement.

When Aunt Betty was satisfied that justice had been served, she told me to get off the chair. My legs trembled as I stood, and I struggled to compose myself, wiping away tears with the back of my hand. She led me back into the lounge, where I was instructed to stand in the corner and “compose myself.” I stood there, sniffling, my face burning with embarrassment, acutely aware of the eyes of the other children on me. Dignity was a distant memory, replaced by a desperate desire to disappear.

After a few minutes, Aunt Betty returned, her expression softened. She asked if I thought I had deserved my punishment. I blushed, the heat rising to my ears, but I managed to nod. In that moment, I understood the strange logic of childhood justice—harsh, but somehow fair. Looking back now, I can almost laugh at the memory, though at the time it felt like the end of the world. Yet, as soon as I was released, I wiped my eyes, squared my shoulders, and went back outside to join Dennis, Gavin, and the others. The sun was still shining, the world still turning, and the sting of the slipper faded as quickly as the memory of pain. Children are nothing if not resilient. And from that day on, I never looked at a slipper the same way again.