Ingrid, our family maid, was more than just a caretaker—she was a force of nature, a woman whose presence seemed to fill every corner of our Somerset home in the late 1960s. She had come to England from Jamaica, leaving behind her own family and three children, to work for my parents. Ingrid was tall and broad-shouldered, her deep brown skin glowing against the starched, boldly patterned dresses she wore. Her hair was always wrapped in a vibrant scarf, and her eyes—so expressive—could shift from stern to sparkling with laughter in a heartbeat. She moved with a purposeful grace, her back always straight, her steps measured and confident. When Ingrid entered a room, you felt it: a hush would fall, and even the most unruly child would pause, sensing her quiet authority. There was a warmth in her smile, a deep well of kindness, but also a firmness in her jaw that let you know she would not tolerate nonsense. She was the kind of adult who could make you feel safe and loved, but also keep you in line with just a look.

Ingrid’s experience as a mother was evident in everything she did. She had raised three children of her own in Jamaica, and her approach to discipline was shaped by both her upbringing and the times. In those days, a smack on the bottom was considered a normal part of child-rearing, and Ingrid made no secret of the fact that her own children had received the same treatment. She would often say, “My children got the same, and they turned out just fine.” There was a sense of fairness in her discipline—she never acted out of anger, but out of a desire to teach and guide. Her methods were firm, but never cruel, and she always made sure you understood why you were being punished.

(short pause) One afternoon stands out in my memory, a day when I truly tested Ingrid’s patience and paid the price. My younger sister and I were playing in the living room, surrounded by the chaos of toys and the swirling patterns of psychedelic wallpaper that seemed to pulse with color in the afternoon light. The house was filled with the distant sound of a Beatles record playing in another room, and the air smelled faintly of furniture polish and the flowers from Ingrid’s dress. In a moment of mischief, I grabbed a bright red crayon and began to draw all over the wallpaper, adding my own swirls and flowers to the already dizzying design. I was so absorbed in my “artwork” that I didn’t hear Ingrid’s footsteps approaching. Suddenly, her shadow fell across me, and I froze, crayon still in hand. Ingrid’s eyes narrowed, her lips pressed into a thin line. She didn’t raise her voice—she didn’t need to. With a calm, measured tone, she told me to put down the crayon and come to her. My heart pounded as I shuffled across the shaggy carpet, cheeks burning with shame and fear. Ingrid sat on the edge of the sofa, took me firmly by the wrist, and guided me over her lap. The scent of her dress and the coolness of the air on the seat of my shorts are memories that have never faded. Her broad palm landed with a sharp, stinging smack, the sound echoing in the room. I bit my lip, determined not to cry, but each smack seemed to sting more than the last. Ingrid never lost her composure—her voice was gentle but firm as she explained why what I’d done was wrong. When it was over, she helped me up, smoothed my hair, and told me to fetch a damp cloth to help clean the wall. My bottom throbbed, but what lingered most was the sense of justice in her discipline—stern, but never unkind.

As I grew older, I began to reflect on those moments, trying to understand the woman behind the discipline. I became increasingly curious about Ingrid’s own children, and how she had raised them back in Jamaica. At night, lying in bed, I would imagine her three children—Winston, the eldest, Gilbert, the mischievous one, and their sister—lined up in their hand-me-down clothes, waiting their turn over Ingrid’s lap. I pictured the sounds of sharp slaps echoing through a house filled with the rhythms of reggae and the scent of Sunday stew simmering on the stove. I wondered if they, too, had felt the same mix of fear and love, of shame and comfort, that I had felt in Ingrid’s care.

My curiosity eventually got the better of me, and I began to ask Ingrid about her methods at home. At first, she just laughed and waved me off, as if it was all part of the era’s unspoken rules. But there was a knowing smile on her lips, and I could tell she was pleased by my interest. After a few more questions—and, admittedly, a few more sore bottoms—she finally agreed to share her stories with me.

Ingrid would settle into her favorite armchair, the one with bold floral upholstery that seemed to swallow her up, and I would sit at her feet, eager to listen. From that vantage point, I could see her broad lap and strong hands—both very familiar to me. She would begin to talk, her voice rich with memory and pride.

She spoke first of her two sons—Winston, the eldest, responsible and serious, and Gilbert, the younger, whose mischievous streak kept her on her toes. “Winston was always trying to set a good example,” Ingrid said, her eyes softening. “But Gilbert—oh, that boy! He needed his bottom smacked more often than not.” She would shake her head, a fond smile playing at her lips. “And believe me, when it was time to tan his hide, he got it good.”

Ingrid described the rules she set in her Jamaican household with a sense of pride. “My house had rules, and everyone knew them. No running inside, no talking back, and chores done before play. If you broke a rule, you knew what was coming.” She explained that discipline was never a surprise—her children always knew the boundaries, and she made sure to explain them clearly. “I’d sit them down, look them in the eye, and tell them, ‘This is what I expect. If you cross the line, you’ll answer for it.’” She believed in fairness and consistency, and her children learned quickly that she meant what she said.

Mischief was a daily occurrence, especially with Gilbert. “That boy was always up to something,” Ingrid said, her voice a mix of exasperation and affection. “One time, he and Winston tried to sneak mangoes from the neighbor’s tree. They thought they were clever, but I saw the juice on their shirts and the seeds in their pockets.” She laughed, the sound warm and full of life, but her tone turned serious as she continued. “I lined them up, and they both got a good talking-to first. Then, over my lap they went—one after the other. I used my hand most days, but if they’d really crossed the line, I had my trusty slipper. It was an old leather one, heavy and worn, and they knew the sight of it meant business.” She described the ritual of discipline—the way she would call them by name, the way they would shuffle forward, heads bowed, knowing what was coming. The slipper, she said, was reserved for the worst offenses, and its presence alone was often enough to keep her boys in line.

For the most serious misdeeds, Ingrid would fetch a tamarind switch from the garden. “Cutting a switch was a ritual,” she explained. “I’d make them watch as I chose the branch, so they’d know I meant it. The switch stung, but it was quick, and I always told them why they were getting it. ‘You must learn respect,’ I’d say. ‘Not just for me, but for yourself and others.’” She described the way the boys would stand silently, watching her select the branch, their faces solemn. The anticipation was often worse than the punishment itself, and Ingrid believed that the lesson was as much about respect and responsibility as it was about pain.

She recounted a story about Winston, who once skipped school to go swimming in the river with friends. “When I found out, I waited for him at the door. He tried to lie, but I could smell the river on him. I made him fetch the switch himself. He cried before it even started, but I gave him three sharp licks and then held him close after. He never skipped school again.” Ingrid’s voice softened as she described holding her son, comforting him after the punishment. She believed that discipline should always be followed by reassurance, a reminder that love was at the heart of every lesson.

Gilbert, on the other hand, was notorious for backchat. “He’d mutter under his breath, thinking I couldn’t hear. I’d catch him, and he’d get a smack with the slipper—right there in the kitchen, with the smell of curry goat in the air and the radio playing ska. He’d sulk for a while, but he always came around for a hug later.” Ingrid’s stories were filled with the sounds and smells of her Jamaican home—the laughter of children, the sizzle of food on the stove, the music that filled every room. Discipline was woven into the fabric of daily life, a constant reminder of the boundaries that kept her family safe and strong.

Ingrid explained that discipline in her home was about love and respect, not fear. “Afterwards, I’d always talk to them, make sure they understood. I’d say, ‘I do this because I love you, and I want you to grow up right.’ In Jamaica, that’s how it was done. The whole neighborhood knew—if you heard a child crying, you knew they were learning a lesson.” She believed that children needed structure and guidance, and that discipline, when done with love, was a gift.

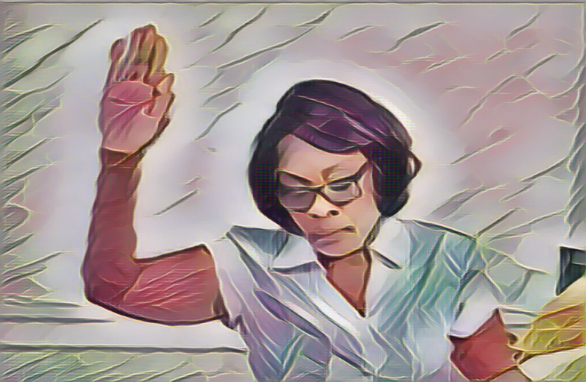

She raised her right palm for emphasis, her voice full of conviction. “This is what I used most of the time. You know yourself how much it stings, young master, especially on a boy’s bottom in those days.” She would smile at me, a twinkle in her eye, and I would nod, remembering all too well the lessons I had learned at her hand.

“If he’d been really bad, though, I’d cut a switch from the garden and give him a proper whipping—like the time the bobbies brought him home for causing trouble in town. He didn’t sit comfortably for days after that!” Ingrid’s stories were never told with malice or regret, but with a sense of pride in the children she had raised and the lessons she had taught. Her discipline was firm, but her love was fiercer still, and in her care, we all learned the value of respect, responsibility, and forgiveness.