In the Johnson household, the slipper was as much a part of the scenery as the lava lamp glowing in the corner or the Beatles records spinning merrily on the gramophone. My parents, Linda and John, both raised in the age of resolute hands and even more resolute rules, passed down their own particular brand of discipline to me and my siblings—Susan, Michael, and David. The slipper was as familiar to us as the Sunday roast or the annual pilgrimage to Brighton Beach. This curious custom, if one could call it that, was hardly unique; it was woven into the tapestry of our 1960s suburb, a golden thread running through every home on our street.

I, Karen, found myself echoing this pattern with my own children, and I know Susan and Michael have done the same with theirs—though, out of respect for privacy, I shall leave the younger ones out of this tale. Smacking, in all its forms, was as common as bell-bottom trousers and scraped knees when my parents were young. In my own childhood, it was still the norm, though perhaps a little softened by the changing times. By the time my children were small, it had become less frequent, but it certainly had not vanished, no matter what the evening news might have said.

My father John’s stories of his own boyhood discipline were legendary. His father, David Senior, a stern man with a bristling moustache and a voice that could silence a room, would administer the belt to his sons’ underpants-clad seats. The ordeal, as recounted over fish and chips, was both terrifying and oddly unifying—a shared experience that left the boys with bruised bottoms and a reluctant respect for authority. The belt, heavy and cracked with age, lived in a drawer in the sideboard, and its mere mention was enough to quell any mischief.

I remember one particular incident when my brother Michael received a belting from Grandfather David. The aftermath became family legend: John and David Senior in a heated argument, voices echoing through the house, while Michael nursed a constellation of little bruises down one side of his bottom. The rest of us watched in awe, our own behaviour miraculously improved for weeks. None of us dared cross Grandfather again; the memory of that day lingered like the scent of aftershave in the hallway.

My mother Linda’s upbringing was a different world altogether. An only child, she was raised in a comfortable, middle-class home, her days divided between the order of boarding school and the strict regime of Nanny Susan when she was home. The school, surprisingly progressive for the 1940s, eschewed corporal punishment in favour of emotional shaming and subtle manipulation—a fact that astonished me when she first revealed it. Yet, at home, Nanny Susan ruled with a cane, and discipline was meted out with a precision that bordered on ceremony.

Linda would describe, in hushed tones, the ritual of her punishments: six sharp strokes on the hands, followed by further sets of six on her bottom and thighs if the offence warranted it. The anticipation was often worse than the punishment itself. She would stand, trembling, in the library, the scent of leather-bound books and polished wood filling her nostrils, as she bent over the arm of the chair. Her hands would already be stinging, and she knew her bottom was next. She often told us, with a wry smile, how fortunate we girls were to receive only a hand-smacking from her.

We seldom saw Nanny Susan and Grandfather David Senior when I was a child; they were distant, both in geography and affection. Yet I remember one visit when Nanny, her hair perfectly coiffed and her eyes sharp as ever, told Linda she was not too old for a thrashing. The remark was delivered with a twinkle, but it made my ears prick up all the same. The old ways, it seemed, were never far from the surface.

In our own home, discipline followed a strict division: John dealt with the boys, Linda with the girls. The boys would be summoned to the study, where John would administer the belt over their underwear—a lighter version of his own childhood punishments, but still enough to leave their bottoms red for a short while. They always insisted it was not so bad, and the colour faded quickly, but the lesson lingered.

For Susan and me, Linda’s hand was the instrument of correction. We would be placed firmly across her lap, our faces burning with embarrassment, especially as these punishments were often delivered in full view of whoever happened to be present. There was no ceremony, no warning—just a swift, decisive action that left us both chastened and oddly relieved, as though a summer storm had passed.

The smacking I remember most vividly happened when I was nine, on a golden summer’s afternoon. (pause) The day had been one of those rare, perfect ones, the sort that seem to stretch on forever, filled with the scent of cut grass and the distant drone of bees. I had been playing outside with a group of friends—Michael, Susan, and David—our games growing ever more boisterous as the sun climbed higher. When Linda called us in for tea, I, emboldened by the presence of my companions and the delicious sense of rebellion that sometimes overtakes a child, refused to obey. (pause: 0.3s) My friends, sensing the drama, fell silent, their eyes wide with anticipation.

Linda, her patience finally exhausted, appeared at the front door, her figure framed by the sunlight, hands planted firmly on her hips. There was a certain inevitability in her stride as she crossed the lawn, her expression one of calm determination. Without a word, she took me gently but unyieldingly by the arm and led me to the low brick wall that bordered our garden. (pause) I remember the feel of the warm bricks beneath my hands as she sat down and, with a deftness born of long practice, guided me across her lap. (pause: 0.3s) The world seemed to shrink to that small patch of sunlit pavement, the air heavy with expectation.

I was acutely aware of Michael, Susan, and David, standing in a silent semicircle, their faces a mixture of sympathy, curiosity, and, I suspect, relief that it was not they who were in my position. My cheeks burned with shame, and I felt a curious mixture of indignation and dread. Linda’s hand, cool and steady, rested for a moment on my back. Then, with a briskness that brooked no argument, she delivered a series of sharp, stinging smacks to the seat of my shorts. (pause) Each one landed with a crisp sound that seemed to echo in the stillness, and with every smack, my resolve crumbled a little further.

I tried, valiantly, to maintain my composure, but the sting was real, and the humiliation even more so. Tears pricked at my eyes, and I bit my lip, determined not to give my audience the satisfaction of seeing me cry. When at last it was over, Linda set me on my feet, her face softening as she brushed a stray lock of hair from my forehead. “There now,” she said quietly, “let that be an end to it.” (pause: 0.3s) I nodded, unable to speak, and hurried indoors, my friends parting to let me pass. (pause) The shame lingered far longer than the sting, and for days afterwards, I could not meet their eyes without recalling the scene. Yet, in time, the memory softened, and I came to see it as a rite of passage—one of those small, necessary storms that mark the boundary between childhood and growing up.

School in the 1970s was a world unto itself, governed by its own peculiar codes and customs. Teachers at both primary and middle school were quick to dispense smacks and slaps, sometimes for the most trivial of offences. Over-the-knee smackings were not uncommon, and the headmistresses of both schools kept implements of discipline at the ready—a cane for the boys, a slipper for the girls. I managed to avoid the slipper, though I did once have my hands smacked with a ruler in front of the entire assembly, along with the rest of the rounders team, for a scuffle at a match. The sting was sharp, but the real punishment was the public spectacle.

High school was a different matter. The school itself was not particularly distinguished, and formal corporal punishment was rare. Instead, there was a great deal of ear-pulling, head-slapping, and the occasional board rubber hurled across the classroom. One home economics teacher, Miss Karen, was notorious for smacking the backs of pupils’ thighs in front of the class. It was more humiliating than painful, especially for the boys in their thick school trousers, but it served as a reminder that childhood was not yet behind us.

My final smacking at home came just before I left school. I had managed to avoid punishment for a year or two, but on this occasion, I was brought home by the police after being caught, with a group of girlfriends, in an over-eighteen club in the city. The shame of being escorted home was bad enough, but Linda and John’s fury was something to behold. I knew, even before they spoke, that a reckoning was coming.

This time, Linda abandoned her usual method. Instead of her hand, she wielded her large plastic hairbrush—a formidable weapon in her determined grip. I fought her every step of the way, but she was resolute, and soon I was over her lap, the hairbrush landing with a series of sharp, stinging smacks. The pain was intense, and the bruises lingered for nearly a week. Looking back, I can only admit that I deserved every bit of it, and perhaps more besides.

My husband, David, had a childhood marked by similar experiences. At home, his legs were frequently slapped, and his father, Michael, a man of few words and strong opinions, would occasionally leather him for more serious transgressions. School was no refuge; diagnosed only recently with autism and ADHD, David struggled to fit in and was regularly strapped by teachers. In Newcastle, where he grew up, the belt was favoured over the cane, and discipline was both swift and severe.

Despite these experiences, both David and I came to believe that corporal punishment had done us good. It was, in our view, a necessary part of growing up—a means of instilling respect and boundaries. When it came time to raise our own children, the decision to continue the tradition seemed almost inevitable. We were, I must say, far gentler than our own parents had been, but we believed it was for our children’s benefit.

My eldest daughter, Susan, now grown, delights in recounting the tale of her first smacking. She was marched over my knee for six firm smacks on the seat of her knickers. When it was over, she leapt up, clutching her bottom, and declared, with great indignation, “My bottom has fallen off!” before hurrying away in tears. David and I, unable to contain ourselves, dissolved into laughter—though we waited until she was out of earshot, of course.

My oldest grandchild, Michael, now twenty-three, is a gentle, sensitive soul. From the start, it was clear that smacking would do him no good at all; indeed, it would likely have caused more harm than benefit. He was raised with a softer touch, and has grown into a thoughtful, compassionate young man.

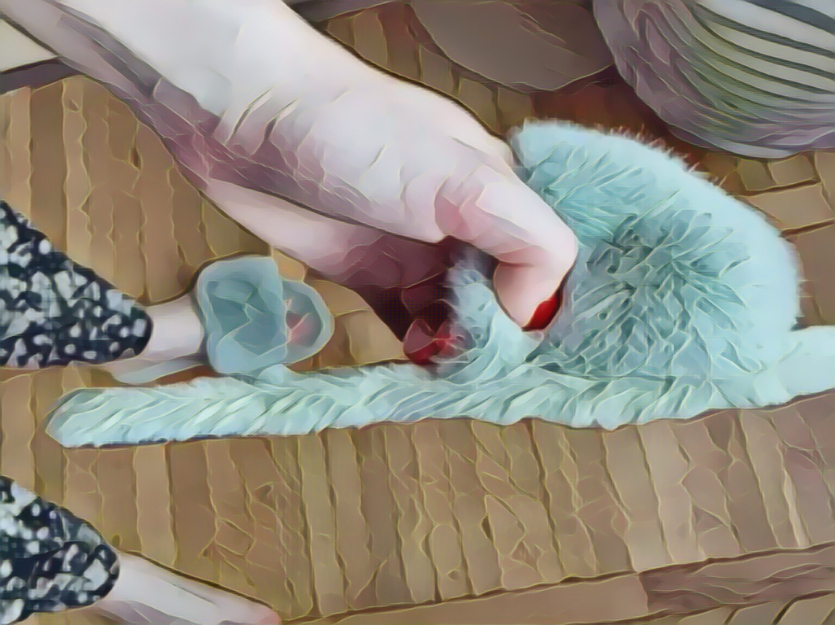

His younger sister, Karen, by contrast, is a force of nature—brilliant, passionate, and endlessly headstrong. For her, nothing but a firm hand would suffice. She was, as a child, a whirlwind of energy and mischief, and only a proper, over-the-knee smacking could bring her to heel. Susan and her husband John administered these punishments with care and consistency, perhaps once a month, and I, too, was called upon to lend a hand from time to time. “Grandmother is no pushover!” Karen would say, half in jest, half in warning.

Far from being damaged, Karen has grown into a remarkable young woman. At a recent family gathering, she confided in me that, without the firm discipline she received as a child, she might well have found herself in real trouble. There was no bitterness in her words—only a recognition that, sometimes, a guiding hand, however firm, is the greatest kindness of all.