The instrument of our correction was a small wooden paddle, legendary in our family and known by many names. Sometimes it was the Family Bottom Smacker—though, as far as I know, only the children ever felt its sting. Most often, it was called the ‘Naughty Spoon,’ a novelty gift from my grandmother, purchased during a windswept day at the Blackpool seaside. But the name that always made us shiver was the Nanny Smacker, boldly painted on the paddle itself, right above a cartoon of a weeping boy, .

The Nanny Smacker was a peculiar relic—about the size of a hairbrush’s back, eight inches long and three wide, with a rounded end and a stubby, well-worn handle. Crafted from solid, polished beechwood, it gleamed with a honey-golden warmth, its surface smooth except for the nicks and dents of long use. A faded red ribbon, tied in a drooping bow, wrapped the handle, its color dulled by time. The front bore that unforgettable image. Above, in bold, hand-painted letters, it read “Nanny Smacker .” On the back, my grandmother’s looping script declared, “To my darling daughter, for when words aren’t enough.”

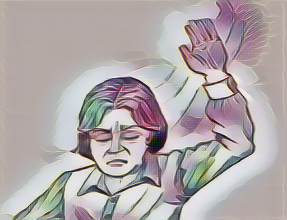

(short pause) I can still recall one golden, humid afternoon, when the kitchen shimmered with the scent of salt and fresh-baked bread. My sister and I were squabbling over a game of checkers, our voices rising until the clatter of pieces echoed through the house. Suddenly, my mother’s footsteps sounded in the hallway—measured, deliberate. She appeared in the doorway, the Nanny Smacker already in her hand, her face stern but not without kindness. My heart pounded, a cold knot of dread tightening in my stomach as she called my name. My cheeks burned, my hands trembled as I shuffled forward, the floorboards creaking beneath my bare feet. She sat on the old wooden chair by the window, sunlight glinting off the paddle’s polished surface. With a gentle but unyielding grip, she guided me across her lap. The world shrank to a patch of sunlight on the floor and the sound of my own breath. Then came the sharp, stinging crack of the paddle—a sound that filled the room and echoed in my ears. The pain was instant, a hot, prickling burn that brought tears to my eyes. I bit my lip, determined not to cry, but a few tears escaped anyway. My sister watched from the doorway, wide-eyed and silent. When it was over, my mother helped me up, smoothing my hair and giving me a quick, tight hug. My bottom throbbed, and I felt a strange mix of relief, embarrassment, and a lingering sting as I hurried off to the bathroom to inspect the damage. Later, my sister and I would compare our red marks in the mirror, half-laughing, half-sniffling, the memory of the paddle’s crack still ringing in our ears.

Whenever the Nanny Smacker was brought out, it made a sharp, unmistakable crack—like thunder in a small room. That sound alone could freeze us in our tracks. Afterward, your bottom would tingle and burn, as if it had been set alight, and we’d joke that all that heat could launch a rocket to the moon. My sister and I would sometimes compare our “battle scars” in the mirror, giggling through our tears, teasing each other about who had the “bravest bum.”

The Nanny Smacker was woven into our family lore. My uncle once claimed he’d hidden it in the flour bin to save himself, only for my mother to find it dusted white. My father, with a twinkle in his eye, would sometimes threaten to “auction it off to the highest bidder” when we were especially unruly, though we all knew it was just a joke. The paddle usually hung on a hook behind the kitchen door, always in plain sight—a silent reminder to behave. When guests visited, my mother would tuck it away in a drawer, but we always knew exactly where it was.

My sister and I were always punished in front of each other, and more often than not, we both received our share. That little paddle kept us in line all the way through adolescence—until, one day, it simply vanished.

It wasn’t until after my mother passed away, as I was sorting through her things, that I found the Nanny Smacker again, tucked away at the bottom of a box of oddments—a relic of childhood, both dreaded and strangely cherished.