The Times, London, 8 February 1910

[Editorial opinion]

.

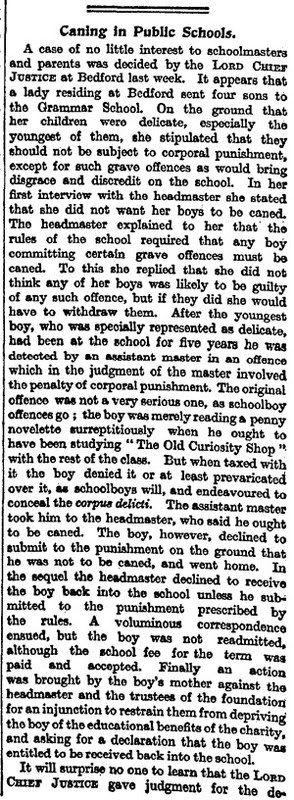

A case of no little interest to schoolmasters and parents was decided by the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE at Bedford last week. It appears that a lady residing at Bedford sent four sons to the Grammar School. On the ground that her children were delicate, especially the youngest of them, she stipulated that they should not be subject to corporal punishment, except for such grave offences as would bring disgrace and discredit on the school. In her first interview with the headmaster she stated that she did not want her boys to be caned. The headmaster explained to her that the rules of the school required that any boy committing certain grave offences must be caned. To this she replied that she did not think any of her boys was likely to be guilty of any such offence, but if they did she would have to withdraw them. After the youngest boy, who was specially represented as delicate, had been at the school for five years, he was detected by an assistant master in an offence which in the judgment of the master involved the penalty of corporal punishment. The original offence was not a very serious one, as schoolboy offences go; the boy was merely reading a penny novelette surreptitiously when he ought to have been studying “The Old Curiosity Shop” with the rest of the class. But when taxed with it the boy denied it or at least prevaricated over it, as schoolboys will, and endeavoured to conceal the corpus delicti. The assistant master took him to the headmaster, who said he ought to be caned. The boy, however, declined to submit to the punishment on the ground that he was not to be caned, and went home. In the sequel the headmaster declined to receive the boy back into the school unless he submitted to the punishment prescribed by the rules. A voluminous correspondence ensued, but the boy was not readmitted, although the school fee for the term was paid and accepted. Finally an action was brought by the boy’s mother against the headmaster and the trustees of the foundation for an injunction to restrain them from depriving the boy of the educational benefits of the charity, and asking for a declaration that the boy was entitled to be received back into the school. It will surprise no one to learn that the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE gave judgment for the defendants with costs. We have refrained from giving the name of the boy because no one would wish him to suffer in repute by reason of his mother’s not very wise proceeding. As the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE said in his very considerate judgment, there was no stain on the boy’s character because of this unfortunate discussion and there was no question of expulsion or any discredit of that kind being cast upon him. We have said that the original offence was not a very serious one in itself. Boys will be boys, and probably most of us when we were at school have done much the same thing many a time. But certainly those of us who were at school in the early or mid-Victorian period would have expected to be caned or birched for it, even without the prevarication and concealment, if we were found out, and would have taken our punishment all in the day’s work. Very likely, too, we should have done what this boy did and tried to conceal or deny our offence. It is all very wrong, no doubt, as we should all admit in maturer years, but it is just because the code of honour and veracity among schoolboys is rather an elastic one that the cane is so useful and salutary a corrective for it. Every schoolboy knows that, administered as the headmaster said he would have administered it in this case, the punishment does not hurt very much; but the sting of it is quite sufficient to make a boy remember that prevarication and deception do not pay, and if the boy has any good moral stuff in him the rarity and solemnity of the ceremonial are very well adapted to bring him to a better frame of mind. All this will be readily admitted by those of us who were at school in those robuster days when the birch or cane was the normal and ever-present symbol of the schoolmaster’s authority in the school. We did not fear it much for the physical pain it inflicted, though that was sharp enough at the moment, and probably much sharper than it is in this more squeamish age. But we did fear it because of the appeal it made to our self-respect, because it came as a sharp and salutary reminder that we had been disgraced before our school-fellows, disgraced not by the mere infliction of corporal punishment, but by the feeling that we had fallen away from a standard of conduct which we knew in our heart of hearts to be that which we ought to act up to. It is hard to see how this physical instrument of moral correction can be altogether dispensed with in the discipline of schoolboys. Their moral sense for the most part is all in the rough; it conforms to an esoteric code of its own, and it needs shaping, polishing, pointing, and directing into conformity with a standard of conduct which it instinctively recognizes but does not always succeed in attaining. Every schoolboy who is worth his salt knows that the words video meliora proboque, deteriora sequor are an epitome of his school life. His forefathers also know, even if he does not, that the argumentum baculinum, judiciously and opportunely applied, is a very salutary agency for teaching him to ensue the meliora and eschew the deteriora. This particular issue was not of course directly raised in the case decided by the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE at Bedford, but it lay indirectly at the back of it. The plaintiff lady’s original objection lay not to corporal punishment as such, but to the corporal punishment of a particular boy or boys who were alleged to be too delicate to sustain it without injury to health. On this point medical evidence was called, but it is reported to have been conflicting. We should conjecture that the original objection might never have been taken but for a conviction entertained by the plaintiff, as it is by many a fond mother in these days, that corporal punishment, even in the form of a mild dose of the cane, is a bad thing in itself. By this conviction, so far as it existed, and at any rate by the belief of the mother, not sustained by undisputed medical testimony, that the boy’s health would suffer from the infliction of three or four cuts of the cane administered through his clothes, the boy himself has been made to suffer much more severely, albeit indirectly and consequentially, than if he had taken his punishment like any other boy and thereby purged his offence once for all. He has been brought into quite unmerited publicity as a boy who had to leave his school because his mother would not allow him to be caned, and he is hardly likely to meet with a very friendly reception at any other school to which his mother may now desire to send him. We may agree with the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE that his mother was prompted by the highest motives, and yet also feel very strongly that she took an exaggerated view of her rights and raised an unfortunate discussion which, although it leaves no stain on the boy’s character, can hardly fail to render his future career as a schoolboy less happy than it otherwise might have been. The moral of it all is, perhaps, that parents, and especially mothers, should be less squeamish than they seem to be nowadays about the necessary punishments of a public school. We do not live in the days of BUSBY nor even in the days of KEATE, and perhaps it is as well that we do not. For this very reason the birch or cane in the hands of a modern schoolmaster is never an instrument of torture, though if certain fond and foolish mothers were to have their way it would soon cease to be an effective and salutary agency of discipline.

A case of no little interest to schoolmasters and parents was decided by the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE at Bedford last week. It appears that a lady residing at Bedford sent four sons to the Grammar School. On the ground that her children were delicate, especially the youngest of them, she stipulated that they should not be subject to corporal punishment, except for such grave offences as would bring disgrace and discredit on the school. In her first interview with the headmaster she stated that she did not want her boys to be caned. The headmaster explained to her that the rules of the school required that any boy committing certain grave offences must be caned. To this she replied that she did not think any of her boys was likely to be guilty of any such offence, but if they did she would have to withdraw them. After the youngest boy, who was specially represented as delicate, had been at the school for five years, he was detected by an assistant master in an offence which in the judgment of the master involved the penalty of corporal punishment. The original offence was not a very serious one, as schoolboy offences go; the boy was merely reading a penny novelette surreptitiously when he ought to have been studying “The Old Curiosity Shop” with the rest of the class. But when taxed with it the boy denied it or at least prevaricated over it, as schoolboys will, and endeavoured to conceal the corpus delicti. The assistant master took him to the headmaster, who said he ought to be caned. The boy, however, declined to submit to the punishment on the ground that he was not to be caned, and went home. In the sequel the headmaster declined to receive the boy back into the school unless he submitted to the punishment prescribed by the rules. A voluminous correspondence ensued, but the boy was not readmitted, although the school fee for the term was paid and accepted. Finally an action was brought by the boy’s mother against the headmaster and the trustees of the foundation for an injunction to restrain them from depriving the boy of the educational benefits of the charity, and asking for a declaration that the boy was entitled to be received back into the school. It will surprise no one to learn that the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE gave judgment for the defendants with costs. We have refrained from giving the name of the boy because no one would wish him to suffer in repute by reason of his mother’s not very wise proceeding. As the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE said in his very considerate judgment, there was no stain on the boy’s character because of this unfortunate discussion and there was no question of expulsion or any discredit of that kind being cast upon him. We have said that the original offence was not a very serious one in itself. Boys will be boys, and probably most of us when we were at school have done much the same thing many a time. But certainly those of us who were at school in the early or mid-Victorian period would have expected to be caned or birched for it, even without the prevarication and concealment, if we were found out, and would have taken our punishment all in the day’s work. Very likely, too, we should have done what this boy did and tried to conceal or deny our offence. It is all very wrong, no doubt, as we should all admit in maturer years, but it is just because the code of honour and veracity among schoolboys is rather an elastic one that the cane is so useful and salutary a corrective for it. Every schoolboy knows that, administered as the headmaster said he would have administered it in this case, the punishment does not hurt very much; but the sting of it is quite sufficient to make a boy remember that prevarication and deception do not pay, and if the boy has any good moral stuff in him the rarity and solemnity of the ceremonial are very well adapted to bring him to a better frame of mind. All this will be readily admitted by those of us who were at school in those robuster days when the birch or cane was the normal and ever-present symbol of the schoolmaster’s authority in the school. We did not fear it much for the physical pain it inflicted, though that was sharp enough at the moment, and probably much sharper than it is in this more squeamish age. But we did fear it because of the appeal it made to our self-respect, because it came as a sharp and salutary reminder that we had been disgraced before our school-fellows, disgraced not by the mere infliction of corporal punishment, but by the feeling that we had fallen away from a standard of conduct which we knew in our heart of hearts to be that which we ought to act up to. It is hard to see how this physical instrument of moral correction can be altogether dispensed with in the discipline of schoolboys. Their moral sense for the most part is all in the rough; it conforms to an esoteric code of its own, and it needs shaping, polishing, pointing, and directing into conformity with a standard of conduct which it instinctively recognizes but does not always succeed in attaining. Every schoolboy who is worth his salt knows that the words video meliora proboque, deteriora sequor are an epitome of his school life. His forefathers also know, even if he does not, that the argumentum baculinum, judiciously and opportunely applied, is a very salutary agency for teaching him to ensue the meliora and eschew the deteriora. This particular issue was not of course directly raised in the case decided by the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE at Bedford, but it lay indirectly at the back of it. The plaintiff lady’s original objection lay not to corporal punishment as such, but to the corporal punishment of a particular boy or boys who were alleged to be too delicate to sustain it without injury to health. On this point medical evidence was called, but it is reported to have been conflicting. We should conjecture that the original objection might never have been taken but for a conviction entertained by the plaintiff, as it is by many a fond mother in these days, that corporal punishment, even in the form of a mild dose of the cane, is a bad thing in itself. By this conviction, so far as it existed, and at any rate by the belief of the mother, not sustained by undisputed medical testimony, that the boy’s health would suffer from the infliction of three or four cuts of the cane administered through his clothes, the boy himself has been made to suffer much more severely, albeit indirectly and consequentially, than if he had taken his punishment like any other boy and thereby purged his offence once for all. He has been brought into quite unmerited publicity as a boy who had to leave his school because his mother would not allow him to be caned, and he is hardly likely to meet with a very friendly reception at any other school to which his mother may now desire to send him. We may agree with the LORD CHIEF JUSTICE that his mother was prompted by the highest motives, and yet also feel very strongly that she took an exaggerated view of her rights and raised an unfortunate discussion which, although it leaves no stain on the boy’s character, can hardly fail to render his future career as a schoolboy less happy than it otherwise might have been. The moral of it all is, perhaps, that parents, and especially mothers, should be less squeamish than they seem to be nowadays about the necessary punishments of a public school. We do not live in the days of BUSBY nor even in the days of KEATE, and perhaps it is as well that we do not. For this very reason the birch or cane in the hands of a modern schoolmaster is never an instrument of torture, though if certain fond and foolish mothers were to have their way it would soon cease to be an effective and salutary agency of discipline.